the-odin-journal

JavaScript

Printing

console.log("Hello, JavaScript")

Variables

let

"use strict"; // prevents use of variables withour declaring it

num = 5; // error: num is not defined

let num =5; // valid

const

-

Use

camelCasemostly. -

To declare a constant (unchanging) variable, use

constinstead ofletconst myBirthday = '18.04.1982'; myBirthday = '01.01.2001'; // error, can't reassign the constant! -

Declare difficult to remember values (hard-coded) in UPPERCASE (community practice), e.g.

const COLOR_RED = "#F00"; -

For others, e.g. constants are calculated in run-time use lowercase

const pageLoadTime = /* time taken by a webpage to load */;The value of

pageLoadTimeis not known before the page load, so it’s named normally. But it’s still a constant because it doesn’t change after the assignment.const BIRTHDAY = '18.04.1982'; // hard-coded const AGE = calculateAge(BIRTHDAY); // calculated in runtime -

Use meaningful and verbose names like

userNameorshoppingCart. Make names maximally descriptive and concise. Examples of bad names aredataandvalue. For exampleourPlanetNameinstead ofplanet, to store current usercurrentUserName. -

Use extra variables whenever needed. An extra variable is good, not evil. Browsers optimize code well enough.

Arithmatic Operations

- Operator precedence

x ** ymeans $x^y$- JavaScript Numbers are Always 64-bit Floating Point

-

let x = 123e5; // 12300000 let y = 123e-5; // 0.00123 -

Integers (numbers without a period or exponent notation) are accurate up to 15 digits.

let x = 999999999999999; // x will be 999999999999999 let y = 9999999999999999; // y will be 10000000000000000Maximum number of decimals is 17. Outside the largest possible number, it shows

Infinityor-InfinitybigIntis used for very huge numbers.const hugeNum = 68509236539n; // Add n at last to declare as bigInt // You can't mix bigInt with normal number type -

Floating point arithmetic is not always 100% correct

let x = 0.2 + 0.1; // 0.30000000000000004 // To solve this, it helps to multiply and divide let x = (0.2 * 10 + 0.1 * 10) / 10; -

JavaScript uses the

+operator for both addition and concatenation. Numbers are added. Strings are concatenated.number+string=stringlet x = 10; let y = 20; let z = "The result is: " + x + y; // The result is: 1020let x = 10; let y = 20; let z = "30"; let result = x + y + z; // 102030 -

JavaScript will try to convert numeric strings to numbers in all numeric operations

let x = "100"; let y = "10"; let z = x / y; // 10 let m = 100 / "5"; // 25 // IMPORTANT // Note "*" or "/" or "-" works, but "+" doesn't, as that means concatenation let w = x + y; //10010 -

Trying to do arithmetic with a non-numeric string will result in

NaN(Not a Number)let x = 100 / "Apple"; // NaNlet x = 100 / "Apple"; isNaN(x); // truelet x = NaN; let y = 5; let z = x + y; //NaNlet x = NaN; let y = "5"; let z = x + y; //NaN5 -

JavaScript interprets numeric constants as hexadecimal if they are preceded by

0x.let x = 0xFF; console.log(x); //255 -

Never write a number with a leading zero (like 07). Some JavaScript versions interpret numbers as octal if they are written with a leading zero.

-

let x = 10; // decimal as default let y = x.toString(2); // base as parameter let z = x.toString(8); console.log(y,z); // 1010 12 -

==(Abstract equality operator) compares after type coercion (conversion)===(Strict equality operator) compares value without type coercion Similarly!==is strict non-equality operator Use only strict operators, it leads to less errorsconsole.log( "5" == 5 ) // true console.log( "5" === 5 ) // false console.log( 5 !== 2+3 ) // false -

To round-off floats,

let lotsOfDecimal = 3.135479876455325; let fixedInt = lotsOfDecimal.toFixed(2); console.log(fixedInt); // 3.14 -

String to number

let myNumber = "74"; myNumber = Number(myNumber); -

Unary

+or unary-converts string to number.let num = "5"; console.log(num, typeof num); // 3 string num = -num; console.log(num, typeof num); // -2 'number' ++or--only applies to variables. Doing5++will give an error

Data Types

There are 8 basic data types in JavaScript.

- Seven primitive data types:

numberfor numbers of any kind: integer or floating-point, integers are limited by±(253-1).bigintfor integer numbers of arbitrary length.stringfor strings. A string may have zero or more characters, there’s no separate single-character type.booleanfortrue/false.nullfor unknown values – a standalone type that has a single valuenull.undefinedfor unassigned values – a standalone type that has a single valueundefined.symbolfor unique identifiers for objects.

- And one non-primitive data type:

objectfor more collection of data and more complex data structures.

The typeof operator allows us to see which type is stored in a variable.

- Usually used as

typeof x, buttypeof(x)is also possible. - Returns a string with the name of the type, like

"string". - For

nullreturns"object"– this is an error in the language, it’s not actually an object.

Strings

-

In JavaScript, you can choose single quotes (

'), double quotes ("), or backticks (`) to wrap your strings in. All will work. -

Strings declared using backticks are a special kind of string called a template literal. In most ways, template literals are like normal strings, but they have some special properties:

- you can embed JavaScript in them

- you can declare template literals over multiple lines

Regular Expressions

Inside a template literal `, you can wrap JavaScript variables or expressions inside ${ }, and the result will be included in the string

const name = "Chris";

const greeting = `Hello, ${name}`;

console.log(greeting); // "Hello, Chris"

In similar way we can do concatenation:

const one = "Hello, ";

const two = "how are you?";

const joined = `${one}${two}`;

console.log(joined); // "Hello, how are you?"

However, template literals make code more readable. RegExp in details. RegExp in 20 mins. When not to use RegExp.

We can use expressions in template literals:

const song = "Fight the Youth";

const score = 9;

const highestScore = 10;

const output = `I like the song ${song}. I gave it a score of ${

(score / highestScore) * 100

}%.`;

console.log(output); // "I like the song Fight the Youth. I gave it a score of 90%."

Multiline Strings

Template literals respect the line breaks in the source code:

// Only works with backticks `

const newline = `One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,`;

console.log(newline);

/*

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

*/

We can also include line break characters (\n), it works with quotes too.

Escape Sequence

To include " or ' or ` we can use escape sequence `\

const bigmouth = 'I\'ve got no balls';

console.log(bigmouth); // I've got no balls

Number <—> String

To convert string to number:

const myString = "123";

const myNum = Number(myString);

console.log(typeof myNum); // number

To convert number to string:

const myNum2 = 123;

const myString2 = String(myNum2);

console.log(typeof myString2); // string

String Methods

All string methods return a new value.

They do not change the original variable.

| Name | Syntax | Notes |

|–|–|–|

| Length | myString.lenght | |

| Extract Char | myString.charAt(position) | |

| Extract UTF-16 Code | myString.charCodeAt(position) | |

| Index Method | myString.at(position) | This is a new addition to JavaScript.

We can use -ve indexes too.

| Property Access | myString[position] | If no character is found, [ ] returns undefined, while charAt() returns an empty string. |

| Substring | myString.slice(strat,end)myString.slice(pos) | slices between start and end pos.

slices pos to end.

If pos -ve, counted from end. |

| | myString.substring(start,end)myString.substring(pos) | Same as slice but -ve pos is considered 0 |

| | myString.substr(start,length)myString.substr(pos) | specifies the length of the extracted part

Single value slices rest of the string from pos. |

| Upper Case | myString.toUpperCase() | |

| Lower Case | myString.toLowerCase() | |

| Concatenation | fullName = firstName.concat(" ",surName) | |

| Trim | myString.trim() | Trims whitespace from both side of string

Leaves inner spaces as it is |

| | myString.trimStart() | |

| | myString.trimEnd() | |

| Padding | myString.padStart(no, str)

myString.padEnd(no, str) | Add no of str to start/end of a string.

To pad a number, convert the number to a string first.

Ref. |

| Repeat | myString.repeat(count) | Returns a string with a number of copies of a string. |

| Replace | myString.replace("Old","New") | Replaces first “Old” with “New”

Case sensitive. |

| | myString.replace(/New/g,”Old”)myString.replaceAll("Old","New") | /g global flag, to replace all occurrences |

| | myString.replace(/NEW/i,”Old”) | Not case sensitive |

| | myString.replace(/NEW/i,”Old”)

myString.replaceAll(/NEW/g,”Old”) | We can use RegExp this way. |

| String —> Array | myString.split(" ")myString.split("") | Splits on spaces.

Returns array of spaces. |

| Includes | myStr.includes(substr) | Returns true/false |

| Search | myStr.search(substr) | Searches a string for a value, or Regexp, and returns the index of the match |

| Starts with

Ends with | myString.startWith(substr)myString.startWith(substr) | Returns true/false |

Complete list of string methods.

- To compare strings use

===, to do it case insensitively check all upper once then all lower once, and return their and.

Evaluate string expression

let str = "15*7/12";

console.log(eval(str)); //8.75

CAUTION: Never use direct eval().

String Object <—> Primitive String

To convert a primitive string to an object: ```javascript let strPrim = “Hello!”; let strObj = new String(strPrim);

console.log(typeof strObj, strObj); // Object String{‘Hello!’}

To convert an object to a primitive string:

```javascript

let strObj = new String("Hello!");

let strPrim = strObj.valueOf();

console.log(typeof strPrim, strPrim); // String Hello!

Emojis and split("")

All the characters in string are UTF-16 codes. But emojis are made of more than one code. So while using split("") in strings with emojis we shiuld be careful, as it’ll break the emoji into several unicodes.

Conditionals

Any value that is not false, undefined, null, 0, NaN, or an empty string ('') returns true when tested as a conditional statement.

Comparison of different types

When comparing values of different types, JavaScript converts the values to numbers:

alert( '2' > 1 ); // true, string '2' becomes a number 2

alert( '01' == 1 ); // true, string '01' becomes a number 1

alert( '2' > '12' ); // true, string dictionary comparision

Avoid Problems:

- The values

nullandundefinedequal==each other and do not equal any other value. - Be careful when using comparisons like

>or<with variables that can occasionally benull/undefined. Checking fornull/undefinedseparately is a good idea.For details refer this.

if, else if, else

Basic syntax:

if (time < 10) {

greeting = "Good morning";

} else if (time < 20) {

greeting = "Good day";

} else {

greeting = "Good evening";

}

Ternary Operator

condition ? run this code if true : run this code if false

const greeting = isBirthday

? "Happy birthday Mrs. Smith — we hope you have a great day!"

: "Good morning Mrs. Smith.";

let message;

if (login == 'Employee') {

message = 'Hello';

} else if (login == 'Director') {

message = 'Greetings';

} else if (login == '') {

message = 'No login';

} else {

message = '';

}

Switch Statement

Equality checks are strict ===

let a = 3;

switch (a) {

case 4:

alert('Right!');

break;

case 3: // (*) grouped two cases

case 5:

alert('Wrong!');

alert("Why don't you take a math class?");

break;

default:

alert('The result is strange. Really.');

}

Logical Operators

OR ||

- Evaluates operands from left to right.

- For each operand, converts it to boolean. If the result is

true, stops and returns the original value of that operand. -

If all operands have been evaluated (i.e. all were

false), returns the last operand.let firstName = ""; let lastName = ""; let nickName = "SuperCoder"; alert( firstName || lastName || nickName || "Anonymous"); // SuperCoder

AND &&

- Evaluates operands from left to right.

-

For each operand, converts it to a boolean. If the result is

false, stops and returns the original value of that operand.alert( 1 && 2 && null && 3 ); // null alert( 1 && 2 && 3 ); // 3, the last one

NOT !

-

Converts the operand to boolean type:

true/false.alert( "non-empty string" ); // true alert( !"" ); // true

Functions

Default parameters

If you’re writing a function and want to support optional parameters, you can specify default values by adding = after the name of the parameter, followed by the default value:

//New Method

function hello(name = "Chris") {

console.log(`Hello ${name}!`);

}

hello("Ari"); // Hello Ari!

hello(); // Hello Chris!

// Old Method

function hello(name) {

if(name == undefined){

name = "Chris";

}

console.log(`Hello ${name}!`);

}

// OR ||

function hello(name) {

name = name || "Chris";

console.log(`Hello ${name}!`);

}

Anonymous Functions

function with no name, funciton expression

// Normal

fucntion logkey(event){

console.log(`You pressed "${event.key}".`);

}

textBox.addEventListener("keydown", logKey);

// Annonymous Functions

textBox.addEventListener("keydown", fuction (event) {

console.log(`You pressed "${event.key}".`);

});

Arrow Functions

Alternate way to write annonymous functions.

// Arrow Functions

textBox.addEventListener("keydown", (event)=> {

console.log(`You pressed "${event.key}".`);

});

// Only one parameter, we can omit ()

textBox.addEventListener("keydown", event=> {

console.log(`You pressed "${event.key}".`);

});

// No prameters

let sayHi = () => alert("Hello!");

sayHi();

// Only one return value

const originals = [1, 2, 3];

const doubled = originals.map(item => item * 2);

console.log(doubled); // [2, 4, 6]

// is similar to

function doubleItem(item) {

return item * 2;

}

let func = (arg1, arg2, ..., argN) => expression;

let func = function(arg1, arg2, ..., argN) {

return expression;

};

let sum = (a, b) => a + b;

let double = n => n * 2;

alert( double(3) ); // 6

// roughly the same as: let double = function(n) { return n * 2 }

Another example with conditional declaration

let welcome = (age < 18) ?

() => alert('Hello!') :

() => alert("Greetings!");

Dynamic parameters

-

Declared Fewer/ More Parameters

If you declare fewer parameters than provided, the extra arguments are ignored. And in case of more pararmeters, rest are taken asundefined.function add(a, b) { console.log(a); // 1 console.log(b); // 2 } add(1, 2, 3, 4); // Extra arguments (3, 4) are ignored. Shows 1 2 add(1); // Shows 1 undefined -

Using

argumentsObject

For non-arrow functions,argumentscan capture all arguments passed.function add() { console.log(arguments); // Outputs: [1, 2, 3, 4] } add(1, 2, 3, 4); -

Using the Rest Operator (

...args)

...argsgathers extra arguments into an array. Works in both regular and arrow functions....is called spread syntax.function add(a, ...args) { console.log(a); // 1 console.log(args); // [2, 3, 4] } add(1, 2, 3, 4);const removeFromArray = function(arr, ...args) { let newArr = []; for(item of arr){ if(args.includes(item)){ continue; } else{ newArr.push(item); } } return newArr; };

nullish coalescing operator

it’s better when most falsy values, such as 0, should be considered “normal”

function showCount(count) {

// if count is undefined or null, show "unknown"

alert(count ?? "unknown");

}

Another example:

const getAge = function (person) {

// The nullish coalescing assignment operator

// only does the assignment if the left side is "nullish" (evaluates to undefined or null)

// if the left side has any other value, no assignment happens

person.yearOfDeath ??= new Date().getFullYear();

return person.yearOfDeath - person.yearOfBirth;

};

Return

function checkAge(age) {

if (age >= 18) {

return true;

} else {

return confirm('Do you have permission from your parents?');

}

}

- When no return statement function returns

undefined.

Function is a value

In js functions are trated as variables.

// Normal method called "Function Declarartion", Most preffered

function sayHi() {

alert( "Hello" );

}

console.log( sayHi ); // prints the function code

function sayHi() {

console.log("Hello");

}

let greet = sayHi; // Assign function to a variable, function expression

greet(); // Hello

sayHi(); // Hello

let greet = function() {

console.log("Hi there!");

};

greet(); // Hi there!

Note: Only use function expressions when you need conditional declaration.

- Function Declarations are processed before the code block is executed. They are visible everywhere in the block.

- Function Expressions are created when the execution flow reaches them.

Callback functions

Functions can be passed as values. The idea is that we pass a function and expect it to be “called back” later if necessary.

So, A callback is simply a function that is passed into another function as an argument.

function ask(question, yes, no) {

if (confirm(question)) yes()

else no();

}

function showOk() {

alert( "You agreed." );

}

function showCancel() {

alert( "You canceled the execution." );

}

// usage: functions showOk, showCancel are passed as arguments to ask

ask("Do you agree?", showOk, showCancel);

// Or Annonymous Expression

ask(

"Do you agree?",

function() { alert("You agreed."); },

function() { alert("You canceled the execution."); }

);

The arguments showOk and showCancel of ask are called callback functions or just callbacks.

Calling before declaration

A global Function Declaration is visible in the whole script, no matter where it is.

That’s due to internal algorithms. When JavaScript prepares to run the script, it first looks for global Function Declarations in it and creates the functions. We can think of it as an “initialization stage”.

And after all Function Declarations are processed, the code is executed. So it has access to these functions.

For example, this works:

sayHi("John"); // Hello, John

function sayHi(name) {

alert( `Hello, ${name}` );

}

The Function Declaration sayHi is created when JavaScript is preparing to start the script and is visible everywhere in it.

…If it were a Function Expression, then it wouldn’t work:

sayHi("John"); // error!

let sayHi = function(name) { // (*) no magic any more

alert( `Hello, ${name}` );

};

Function Expressions are created when the execution reaches them. That would happen only in the line (*). Too late.

Conditional Function Decalrations

let age = 16; // take 16 as an example

if (age < 18) {

welcome(); // \ (runs)

// |

function welcome() { // |

alert("Hello!"); // | Function Declaration is available

} // | everywhere in the block where it's declared

// |

welcome(); // / (runs)

} else {

function welcome() {

alert("Greetings!");

}

}

// Here we're out of curly braces,

// so we can not see Function Declarations made inside of them.

welcome(); // Error: welcome is not defined

We can do:

let age = prompt("What is your age?", 18);

let welcome;

if (age < 18) {

welcome = function() {

alert("Hello!");

};

} else {

welcome = function() {

alert("Greetings!");

};

}

welcome(); // ok now

or simply

let age = prompt("What is your age?", 18);

let welcome = (age < 18) ?

function() { alert("Hello!"); } :

function() { alert("Greetings!"); };

welcome(); // ok now

Function Scope

- the variables and other things defined inside the function are inside their own separate scope

- The top-level outside all your functions is called the global scope. Values defined in the global scope are accessible from everywhere in the code.

- Keeping parts of your code locked away in functions avoids such problems, and is considered the best practice.

For example, say you have an HTML file that is calling in two external JavaScript files, and both of them have a variable and a function defined that use the same name:

html

<!-- Excerpt from my HTML -->

<script src="first.js"></script>

<script src="second.js"></script>

<script>

greeting();

</script>

js

// first.js

const name = "Chris";

function greeting() {

alert(`Hello ${name}: welcome to our company.`);

}

js

// second.js

const name = "Zaptec";

function greeting() {

alert(`Our company is called ${name}.`);

}

Both functions you want to call are called greeting(), but you can only ever access the first.js file’s greeting() function (the second one is ignored). In addition, an error results when attempting (in the second.js file) to assign a new value to the name variable — because it was already declared with const, and so can’t be reassigned.

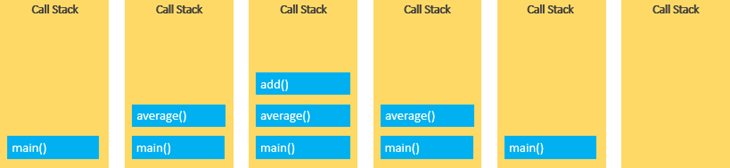

Call Stack

- The call stack works based on the last-in-first-out (LIFO) principle.

- When you execute a script, the JavaScript engine creates a global execution context and pushes it on top of the call stack.

- Whenever a function is called, the JavaScript engine creates a function execution context for the function, pushes it on top of the call stack, and starts executing the function.

- If a function calls another function, the JavaScript engine creates a new function execution context for the function being called and pushes it on top of the call stack.

- When the current function completes, the JavaScript engine pops it off the call stack and resumes the execution where it left off.

- The script will stop when the call stack is empty.

- it can throw soverflow exception when no of function call exceeds limit. eg. infinite recursive call.

- JavaScript is a single-threaded programming language. This means that the JavaScript engine has only one call stack. Therefore, it only can do one thing at a time.

When executing a script, the JavaScript engine executes code from top to bottom, line by line. In other words, it is synchronous.

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

function average(a, b) {

return add(a, b) / 2;

}

let x = average(10, 20);

Arrays

const cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

const cars = [];

cars[0]= "Saab";

cars[1]= "Volvo";

cars[2]= "BMW";

Array are objects in js.

Objects use names to access its “members”. In this example, person.firstName returns John:

const person = {firstName:"John", lastName:"Doe", age:46};

DOM to Array

in DOM node list we can’t use filter, map, etc. So we need to convert it to array frist:

const divs = document.querySelectorAll("div");

let divArray = Arrays.form(divs);

// or

let divArray = Arrays.form(...divs);

// take every element from divs and sperad it in the array

Array Methods

| Method | Syntax | Use |

|–|–|–|

|index|arr[i]|to access i’th index. -ve not allowed|

|at|arr.at(i)|to accesss index. -ve allowed|

| lenght | arr.length ||

|sort|arr.sort()|sorts the array in lexographical order converting to string|

|reverse|arr.reverse()|modifies main array, also returns the reversed array|

|tostring|const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Apple", "Mango"];console.log(fruits.toString())|Banana,Orange,Apple,Mango|

|join|console.log(fruits.join(" * "))|Banana * Orange * Apple * Mango|

|push|arr.push(item)|add new element to array. LIFO|

|pop|arr.pop()|pops last entered element. LIFO|

|shift|fruits.shift()|removes "Banana", Similar to Dequeue, FIFO |

|unshift|fruits.unshift(item)|adds item to start |

|concat|arr1.concat(arr2,arr3)|Merges multiple arrays|

|copyWithin|fruits.copyWithin(2, 0)|Copy to index 2, all elements from index 0:

Banana,Orange,Banana,Orange|

|copyWithin|fruits.copyWithin(2, 0, 2)|Copy to index 2, the elements from index 0 to 2:

Banana,Orange,Banana,Orange,Kiwi,Papaya|

|flat|const myArr = [[1,2],[3,4],[5,6]];const newArr = myArr.flat();| creates a new array with sub-array elements concatenated to a specified depth

1,2,3,4,5,6|

|flatMap|const myArr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6];const newArr = myArr.flatMap(x => [x, x * 10]);|first maps all elements of an array and then creates a new array by flattening the array

1,10,2,20,3,30,4,40,5,50,6,60|

|splice|const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Apple", "Mango"];fruits.splice(2, 0, "Lemon", "Kiwi");|Banana,Orange,Lemon,Kiwi,Apple,Mango

- The first parameter (2) defines the position where new elements should be added (spliced in).

- The second parameter (0) defines how many elements should be removed.

- The rest of the parameters (“Lemon” , “Kiwi”) define the new elements to be added.|

||const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Apple", "Mango"];fruits.splice(2, 2, "Lemon", "Kiwi");|Original Array: Banana,Orange,Apple,Mango

New Array: Banana,Orange,Lemon,Kiwi

Removed Items:Apple,Mango|

|splice() to remove|const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Apple", "Mango"];fruits.splice(0, 1);|Orange,Apple,Mango|

|toSpliced()|const months = ["Jan", "Feb", "Mar", "Apr"];const spliced = months.toSpliced(0, 1);|keeps the main array unchanged|

|slice|const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Lemon", "Apple", "Mango"];const citrus = fruits.slice(1);|- Slice out a part of an array starting from array element 1 (“Orange”):Orange,Lemon,Apple,Mango

- Does not modify main array|

||const fruits = ["Banana", "Orange", "Lemon", "Apple", "Mango"];const citrus = fruits.slice(3);|Apple,Mango|

||const citrus = fruits.slice(1, 3);|Orange,Lemon|

|indexOf|arr.indexOf(item, from)|looks for item starting from index from, and returns the index where it was found, otherwise -1. from defaults to 0. uses ===|

|includes|arr.includes(item, from)|looks for item starting from index from, returns true if found. from defaults to 0.|

|lastIndexOf|arr.lastIndexOf(item, from)|same as indexOf, just checks right to left.|

|find|let result = arr.find(function(item, index, array) {});|returns true/false|

|findIndex|let result = arr.findIndex(callback);|same as find. returns index if found and -1 if not.|

|lastIndexof|let result = arr.lastIndexOf(callback);|same as findIndex, returns last index if found, -1 if not|

|some|arr.some(fn)|The function fn is called on each element of the array similar to map. If any results are true, returns true, otherwise false.|

|every|arr.every(fn)|The function fn is called on each element of the array similar to map. If all results are true, returns true, otherwise false.|

|fill|arr.fill(value, start, end)|fills the array with repeating value from index start to end. |

|copyWithin|arr.copyWithin(target, start, end)|copies its elements from position start till position end into itself, at position target (overwrites existing)|

|flat/faltMap|arr.flat(depth)/arr.flatMap(fn) |create a new flat array from a multidimensional array|

every/some example:

function arraysEqual(arr1, arr2) {

return arr1.length === arr2.length && arr1.every((value, index) => value === arr2[index]);

}

alert( arraysEqual([1, 2], [1, 2])); // true

NOTE

includescorrectly handlesNaN, unlikeindexOfconst arr = [NaN]; alert( arr.indexOf(NaN) ); // -1 (wrong, should be 0) alert( arr.includes(NaN) );// true (correct)

NOTE: methods

sort,reverseandsplicemodify the array itself.Splice

arr.splice(start[, deleteCount, elem1, ..., elemN])It modifies

arrstarting from the indexstart: removesdeleteCountelements and then insertselem1, ..., elemNat their place. Returns the array of removed elements. ```javascript let arr = [“I”, “study”, “JavaScript”, “right”, “now”];

// remove 3 first elements and replace them with another arr.splice(0, 3, “Let’s”, “dance”);

alert( arr ) // now [“Let’s”, “dance”, “right”, “now”]

// Or we can also do let removed = aarr.splice(0, 3, “Let’s”, “dance”); alert( removed ); // [ ‘I’, ‘study’, ‘JavaScript’ ] alert ( arr ); // [“Let’s”, “dance”, “right”, “now”]

Negative index alowed too

```javascript

let arr = [1, 2, 5];

arr.splice(-1, 0, 3, 4);

alert( arr ); // 1,2,3,4,5

Sort

Sorts in lexographical order after converting to string

let arr = [ 1, 2, 15 ];

arr.sort();

alert( arr ); // 1, 15, 2

to sort in our own order, we have to use callback, based on this callback the array is bubbled

function compareNumeric(a, b) {

if (a > b) return 1;

if (a == b) return 0;

if (a < b) return -1;

}

let arr = [ 1, 2, 15 ];

arr.sort(compareNumeric);

alert(arr); // 1, 2, 15

Actually, a comparison function is only required to return a positive number to say “greater” and a negative number to say “less”.

let arr = [ 1, 2, 15 ];

arr.sort( (a, b) => a - b );

alert(arr); // 1, 2, 15

NOTE: Use localCompare for strings ```javascript let countries = [‘Österreich’, ‘Andorra’, ‘Vietnam’];

alert( countries.sort( (a, b) => a > b ? 1 : -1) ); // Andorra, Vietnam, Österreich (wrong)

alert( countries.sort( (a, b) => a.localeCompare(b) ) ); // Andorra,Österreich,Vietnam (correct!)

sorting objects based on property

```javascript

const books = [

{ title: "Book A", year: 2010 },

{ title: "Book B", year: 2005 },

{ title: "Book C", year: 2018 },

];

const booksSortedByYearAsc = books.sort((a, b) => a.year - b.year);

console.log(booksSortedByYearAsc);

// Output:

[

{ title: "Book B", year: 2005 },

{ title: "Book A", year: 2010 },

{ title: "Book C", year: 2018 },

];

Split & join

The str.split(delim) method splits the string into an array by the given delimiter delim.

let names = 'Bilbo, Gandalf, Nazgul';

let arr = names.split(', ');

for (let name of arr) {

alert( `A message to ${name}.` ); // A message to Bilbo (and other names)

}

The split method has an optional second numeric argument – a limit on the array length. If it is provided, then the extra elements are ignored. In practice it is rarely used though:

let arr = 'Bilbo, Gandalf, Nazgul, Saruman'.split(', ', 2);

alert(arr); // Bilbo, Gandalf

The call to split(s) with an empty s would split the string into an array of letters:

let str = "test";

alert( str.split('') ); // t,e,s,t

The call arr.join(glue) does the reverse to split. It creates a string of arr items joined by glue between them.

let arr = ['Bilbo', 'Gandalf', 'Nazgul'];

let str = arr.join(';'); // glue the array into a string using ;

alert( str ); // Bilbo;Gandalf;Nazgul

More Arrays Methods

Map

takes a callback function passes each element to it

function addOne(num) {

return num + 1;

}

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

const mappedArr = arr.map(addOne);

console.log(mappedArr); // Outputs [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

const mappedArr = arr.map((num) => num + 1);

Filter

The filter method expects the callback to return either true or false. If it returns true, the value is included in the output array, if false it’s not.

function isOdd(num) {

return num % 2 !== 0;

}

const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

const oddNums = arr.filter(isOdd);

console.log(oddNums); // Outputs [1, 3, 5];

console.log(arr); // Outputs [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], original array is not affected

Reduce

let value = arr.reduce(function(accumulator, item, index, array) {

// ...

}, [initial]);

accumulator– is the result of the previous function call, equalsinitialthe first time (ifinitialis provided).- if there’s no initial, then

reducetakes the first element of the array as the initial value and starts the iteration from the 2nd element. item– is the current array item.index– is its position.array– is the array.- After last item it returns next

accumulator. ```javascript const arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]; const productOfAllNums = arr.reduce((total, currentItem) => { return total * currentItem; }, 1); // the function can also be written as // (total, currentItem) => total * currentItem

console.log(productOfAllNums); // Outputs 120; console.log(arr); // Outputs [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

// if initialValue given 10, the output would be 1200

### reduceRight

> NOTE The method [arr.reduceRight](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array/reduceRight) does the same but goes from right to left

### Map, Filter, Reduce Together

So what `.reduce()` will do, is it will once again go through every element in `arr` and apply the `callback` function to it. It then changes `total`, without actually changing the array itself. After it’s done, it returns `total`.

Example:

```javascript

// Calculate sum of all even numbers multiplied by 3

function sumOfTripledEvens(array) {

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

// Step 1: If the element is an even number

if (array[i] % 2 === 0) {

// Step 2: Multiply this number by three

const tripleEvenNumber = array[i] * 3;

// Step 3: Add the new number to the total

sum += tripleEvenNumber;

}

}

return sum;

}

// This can be done as

function arrayMethodMagic(array){

return array

.filter( item=> item%2==0 )

.map( item=> item*3 )

.reduce( (total,currentItem)=> total+currentItem );

}

let arr = [1,2,3,4,5];

console.log(sumOfTripledEvens(arr)); // 18

console.log(arrayMethodMagic(arr)); // 18

Array.isArray

Arrays do not form a separate language type. They are based on objects.

So typeof does not help to distinguish a plain object from an array:

alert(typeof {}); // object

alert(typeof []); // object (same)

…But arrays are used so often that there’s a special method for that: Array.isArray(value). It returns true if the value is an array, and false otherwise.

alert(Array.isArray({})); // false

alert(Array.isArray([])); // true

Most methods support “thisArg”

Almost all array methods that call functions – like find, filter, map, with a notable exception of sort, accept an optional additional parameter thisArg.

That parameter is not explained in the sections above, because it’s rarely used. But for completeness, we have to cover it.

Here’s the full syntax of these methods:

arr.find(func, thisArg);

arr.filter(func, thisArg);

arr.map(func, thisArg);

// ...

// thisArg is the optional last argument

The value of thisArg parameter becomes this for func.

For example, here we use a method of army object as a filter, and thisArg passes the context:

let army = {

minAge: 18,

maxAge: 27,

canJoin(user) {

return user.age >= this.minAge && user.age < this.maxAge;

}

};

let users = [

{age: 16},

{age: 20},

{age: 23},

{age: 30}

];

// find users, for who army.canJoin returns true

let soldiers = users.filter(army.canJoin, army);

alert(soldiers.length); // 2

alert(soldiers[0].age); // 20

alert(soldiers[1].age); // 23

If in the example above we used users.filter(army.canJoin), then army.canJoin would be called as a standalone function, with this=undefined, thus leading to an instant error.

A call to users.filter(army.canJoin, army) can be replaced with users.filter(user => army.canJoin(user)), that does the same. The latter is used more often, as it’s a bit easier to understand for most people.

Chech two arrays are equal

function arraysEqual(arr1, arr2) {

return arr1.length === arr2.length && arr1.every((value, index) => value === arr2[index]);

}

alert( arraysEqual([1, 2], [1, 2])); // true

Shuffle

for details check this.

function shuffle(arr){ return arr.sort( () => Math.random() - 0.5 ); } // not the best shuffle algo, has biasness // returns positive negative or zero randomly based on that array is sorted randomlyBetter algo: Fisher-Yates shuffle: ```javascript function shuffle(array) { for (let i = array.length - 1; i > 0; i–) { let j = Math.floor(Math.random() * (i + 1)); // random index from 0 to i

// swap elements array[i] and array[j]

[array[i], array[j]] = [array[j], array[i]];

// "destructuring assignment" syntax, same as

// let t = array[i]; array[i] = array[j]; array[j] = t } } ``` # Loops

for..of loop

const cats = ["Leopard", "Serval", "Jaguar", "Tiger", "Caracal", "Lion"];

for (const cat of cats) {

console.log(cat);

}

for…in loop

for (key in object) {

// executes the body for each key among object properties

}

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

isAdmin: true

};

for (let key in user) {

// keys

alert( key ); // name, age, isAdmin

// values for the keys

alert( user[key] ); // John, 30, true

}

Apart from this for, while, do...while all have regular syntax.

forEach() method

The forEach() method in JavaScript is used to execute a provided function once for each element in an array (or other iterable objects like NodeLists).

array.forEach(function(currentValue, index, array) {

// Code to be executed

});

Parameters:

- currentValue: The value of the current element in the array.

- index (Optional): The index of the current element.

- array (Optional): The array that

forEachwas called on.

Basic usage:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4];

numbers.forEach(function(number) {

console.log(number); // Prints 1, 2, 3, 4

});

Accessing the index and the array:

const fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry'];

fruits.forEach(function(fruit, index) {

console.log(`${index}: ${fruit}`);

});

// Output:

// 0: apple

// 1: banana

// 2: cherry

Modifying array elements

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4];

numbers.forEach((number) => {

number = number * 2;

});

console.log(numbers); // [1, 2, 3, 4]

In this case, number is just a copy of the array element, not a reference to it. When you modify number, it doesn’t affect the original array. This is because JavaScript passes primitive types (like numbers) by value. To tackle this:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4];

numbers.forEach((number, index, array) => {

array[index] = number * 2; // Doubles each element

});

console.log(numbers); // [2, 4, 6, 8]

NOTE:

forEach()does not return a new array (likemap()); it simply iterates over the array and performs an operation on each element.- It cannot be broken or stopped mid-loop like a

forloop (unless usingreturnorthrowwithin a function).- It is not suitable for asynchronous operations (use

map()withPromiseorfor...ofinstead).

break & continue

Syntax constructs that are not expressions cannot be used with the ternary operator ?. In particular, directives such as break/continue aren’t allowed there.

(i > 5) ? alert(i) : continue; // continue isn't allowed here

Labeled break & continue

outer: for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

let input = prompt(`Value at coords (${i},${j})`, '');

// if an empty string or canceled, then break out of both loops

if (!input) break outer; // (*)

// do something with the value...

}

}

alert('Done!');

Labels do not allow us to jump into an arbitrary place in the code.

For example, it is impossible to do this:

break label; // jump to the label below (doesn't work)

label: for (...)

A break directive must be inside a code block. Technically, any labelled code block will do, e.g.:

label: {

// ...

break label; // works

// ...

}

…Although, 99.9% of the time break is used inside loops, as we’ve seen in the examples above.

A continue is only possible from inside a loop.

DOM

When your HTML code is parsed by a web browser, it is converted to the DOM - Document Obejct Model.

NOTE: JavaScript does not alter your HTML, but the DOM - your HTML file will look the same, but the JavaScript changes what the browser renders.

Your JavaScript, for the most part, is run whenever the JS file is run or when the script tag is encountered in the HTML. If you are including your JavaScript at the top of your file, many of these DOM manipulation methods will not work because the JS code is being run before the nodes are created in the DOM. The simplest way to fix this is to include your JavaScript at the bottom of your HTML file so that it gets run after the DOM nodes are parsed and created. Alternatively, you can link the JavaScript file in the

<head>of your HTML document. Use the<script>tag with thesrcattribute containing the path to the JS file, and include thedeferkeyword to load the file after the HTML is parsed, as such:<head> <script src="js-file.js" defer></script> </head>

Query selectors

element.querySelector(selector)- returns a reference to the first match of selector.element.querySelectorAll(selectors)- returns a “NodeList” containing references to all of the matches of the selectors.querySelectorAllreturns a NodeList not an array. NodeList has several array methods missing.

Element creation

document.createElement(tagName, [options])- creates a new element of tag type tagName.const div = document.createElement("div");This function does NOT put your new element into the DOM - it creates it in memory. This is so that you can manipulate the element (by adding styles, classes, ids, text, etc.) before placing it on the page. To add-

Append elements

parentNode.appendChild(childNode)- appends childNode as the last child of parentNode.parentNode.insertBefore(newNode, referenceNode)- inserts newNode into parentNode before referenceNode.

Remove elements

parentNode.removeChild(child)- removes child from parentNode on the DOM and returns a reference to child.

Adding inline style

// adds the indicated style rule to the element in the div variable

div.style.color = "blue";

// adds several style rules

div.style.cssText = "color: blue; background: white;";

// adds several style rules

div.setAttribute("style", "color: blue; background: white;");

// dot notation with kebab case: doesn't work as it attempts to subtract color from div.style.background

// equivalent to: div.style.background - color

div.style.background-color;

// dot notation with camelCase: works, accesses the div's background-color style

div.style.backgroundColor;

// bracket notation with kebab-case: also works

div.style["background-color"];

// bracket notation with camelCase: also works

div.style["backgroundColor"];

Editing attributes

// if id exists, update it to 'theDiv', else create an id with value "theDiv"

div.setAttribute("id", "theDiv");

// returns value of specified attribute, in this case "theDiv"

div.getAttribute("id");

// removes specified attribute

div.removeAttribute("id");

Working with classes, classList

// adds class "new" to your new div

div.classList.add("new");

// removes "new" class from div

div.classList.remove("new");

// if div doesn't have class "active" then add it, or if it does, then remove it

div.classList.toggle("active");

It is often standard (and cleaner) to toggle a CSS style rather than adding and removing inline CSS.

Adding textContent, innerHTML

// creates a text node containing "Hello World!" and inserts it in div

div.textContent = "Hello World!";

// renders the HTML inside div

div.innerHTML = "<span>Hello World!</span>";

Note that using textContent is preferred over innerHTML for adding text, as innerHTML should be used sparingly to avoid potential security risks (JavaScript injection). So avoid innerHTML from user input.

Events

Events are actions that occur on your webpage, such as mouse-clicks or key-presses.

Adding eventListener

Method 1 : Inline Event Attributes in HTML

For specifying function attributes directly in the HTML elements.

<button onclick="alert('Hello World')">Click Me</button>

This solution is less than ideal because we’re cluttering our HTML with JavaScript. Also, we can only set one “onclick” property per DOM element, so we’re unable to run multiple separate functions in response to a click event using this method.

Method 2 : Setting Event Properties in JavaScript

For using on<eventType> properties like onclick or onmousedown directly on DOM nodes

<!-- the HTML file -->

<button id="btn">Click Me</button>

// the JavaScript file

const btn = document.querySelector("#btn");

btn.onclick = () => alert("Hello World");

Can only have one onClick property.

Method 3 (Preferred) : Event Listeners

<!-- the HTML file -->

<button id="btn">Click Me Too</button>

// the JavaScript file

const btn = document.querySelector("#btn");

btn.addEventListener("click", () => {

alert("Hello World");

});

We can have as many event listeners as we want.

NOTE: Use named functions if we’re going to do same thing in multiple places. If we’re going to perform the action only on one event, it’s better to use arrow functions.

Event parameter e

The e parameter in event listeners represents the event object, providing details about the event and access to the target element (e.target). It allows dynamic responses, like modifying the target:

btn.addEventListener("click", (e) => {

console.log(e.target); // <button id="btn">Click Me!</button>

e.target.style.background = "blue"; // Changes background to blue

});

Listeners to group of nodes

<div id="container">

<button id="one">Click Me</button>

<button id="two">Click Me</button>

<button id="three">Click Me</button>

</div>

// buttons is a node list. It looks and acts much like an array.

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll("button");

// we use the .forEach method to iterate through each button

buttons.forEach((button) => {

// and for each one we add a 'click' listener

button.addEventListener("click", () => {

alert(button.id);

});

});

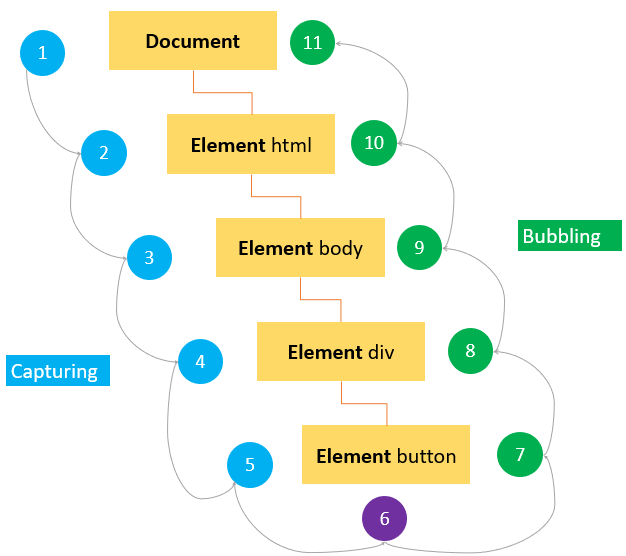

Event Flow

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>JS Event Demo</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="container">

<button id='btn'>Click Me!</button>

</div>

</body>

let btn = document.querySelector('#btn');

btn.addEventListener('click',() => {

alert('It was clicked!');

});

By default, event listeners in JavaScript listen during the bubbling phase, not the capturing phase.

Capturing Phase → Target Phase → Bubbling Phase

Options in addEventListener

element.addEventListener(type, operation, options);

// example

element.addEventListener('click', handler, { capture: true, once: true });

-

capture(Boolean)- Determines if the event is captured during the capturing phase (before bubbling).

- Default:

false.

element.addEventListener('click', handler, { capture: true }); -

once(Boolean)- Ensures the event listener is triggered only once. After being invoked, it is automatically removed.

- Default:

false.

element.addEventListener('click', handler, { once: true });silimar to:

function handler(event) { console.log('Clicked!'); element.removeEventListener('click', handler); // Manually remove the listener } element.addEventListener('click', handler);

Event methods

The following table shows the most commonly used properties and methods of the event object:

| Property / Method | Description | |

|---|---|---|

bubbles |

true if the event bubbles | |

cancelable |

true if the default behavior of the event can be canceled | |

currentTarget |

the current element on which the event is firing | |

defaultPrevented |

return true if the preventDefault() has been called |

|

detail |

more information about the event | |

eventPhase |

1 for capturing phase, 2 for target, 3 for bubbling | |

preventDefault() |

cancel the default behavior for the event. This method is only effective if the cancelable property is true | |

stopPropagation() |

cancel any further event capturing or bubbling. This method only can be used if the bubbles property is true. | |

stopImmediatePropagation() |

stop the event from being handled by any other handlers in the current target. Also stops further event capturing or bubbling. | |

target |

the target element of the event | |

type |

the type of event that was fired |

Note that the event object is only accessible inside the event handler. Once all the event handlers have been executed, the event object is automatically destroyed.

Page Load Events

When you open a page, the following events occur in sequence:

- DOMContentLoaded – the browser fully loaded HTML and completed building the DOM tree. However, it hasn’t loaded external resources like stylesheets and images. In this event, you can start selecting DOM nodes or initialize the interface.

- load – the browser fully loaded the HTML and external resources like images and stylesheets.

When you leave the page, the following events fire in sequence:

- beforeunload – fires before the page and resources are unloaded. You can use this event to show a confirmation dialog to confirm if you want to leave the page. By doing this, you can prevent data loss in case the user is filling out a form and accidentally clicks a link that navigates to another page.

- unload – fires when the page has completely unloaded. You can use this event to send the analytic data or to clean up resources.

addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', (event) => {

console.log('The DOM is fully loaded.');

});

addEventListener('load', (event) => {

console.log('The page is fully loaded.');

});

addEventListener('beforeunload', (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

event.returnValue = ''; // Show a confirmation dialog in Chrome

});

addEventListener('unload', (event) => {

console.log('The page is completely unloaded.');

});

Mouse Events

Mouse Events Overview

mousedown: Fires when a mouse button is pressed on an element.mouseup: Fires when a pressed mouse button is released.click: Fires after onemousedown+ onemouseup.- Skips firing if the button is pressed, moved off, or released outside the element.

dblclick

- Fires on a double-click.

- Sequence:

mousedown→mouseup→click→mousedown→mouseup→click→dblclick

mousemove

- Fires repeatedly as the mouse moves over an element.

- Optimization Tip: Add/remove listeners only when needed to avoid performance issues.

mouseover / mouseout

mouseover: Fires when the mouse enters an element’s boundaries.mouseout: Fires when the mouse leaves an element’s boundaries.

mouseenter / mouseleave

mouseenter: Likemouseover, but does not fire on child elements.mouseleave: Likemouseout, but does not fire when exiting child elements.- Does not bubble.

wheel

- Fires when the mouse wheel or touchpad scrolls.

event.deltaY: Vertical scroll amount (positive for down, negative for up).event.deltaX: Horizontal scroll amount (positive for right, negative for left).event.deltaMode: Units of scrolling:0: Pixels (default).1: Lines.2: Pages.body.addEventListener('wheel', (e) => { console.log(`Scrolled: deltaY = ${e.deltaY}, deltaX = ${e.deltaX}`); });

Detecting Mouse Buttons

event.buttonvalues:0: Left button1: Middle button (wheel)2: Right button3: Browser Back4: Browser Forward

Example: Disable context menu for right-click:

btn.addEventListener('contextmenu', (e) => e.preventDefault());

Modifier Keys

- Keys:

shift,ctrl,alt,meta(Command on Mac). event.<key>: Boolean (trueif pressed).

btn.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

if (e.ctrlKey) console.log('Ctrl key pressed');

});

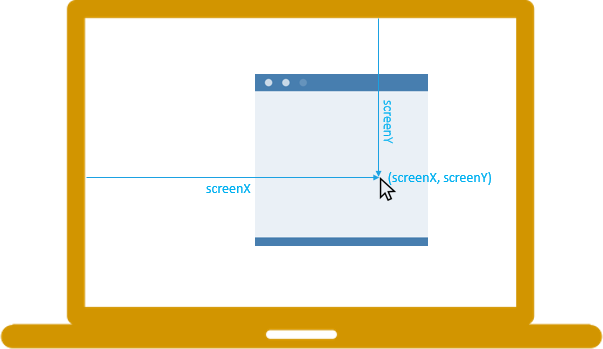

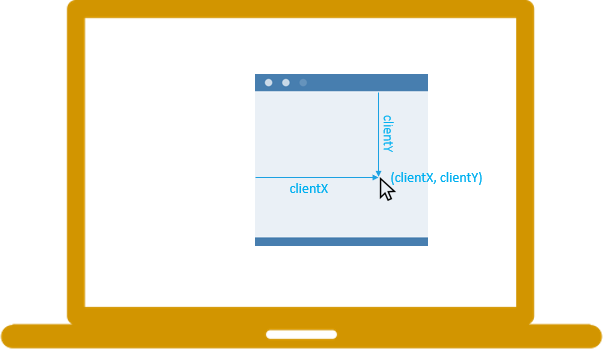

Screen & Client Coordinates

screenX,screenY: Mouse position relative to the screen.clientX,clientY: Position within the application’s client area.

track.addEventListener('mousemove', (e) => {

console.log(`Screen: (${e.screenX}, ${e.screenY})`);

console.log(`Client: (${e.clientX}, ${e.clientY})`);

});

|  |

|  |

|–|–|

|

|–|–|

Keyborad Events

keydown– Fires when a key is pressed and repeats while holding it down.keyup– Fires when a key is released.keypress– Fires for character keys (a, b, c), not for non-character keys (e.g., arrows). Repeats when holding a key. (Deprecated in modern browsers)

Sequence for character keys:

keydown → keypress → keyup

Sequence for non-character keys:

keydown → keyup

let input = document.getElementById('message');

input.addEventListener("keydown", (e) => { /* handle */ });

input.addEventListener("keyup", (e) => { /* handle */ });

Event Properties:

key– Returns the character of the key pressed (e.g.,z).code– Represents the physical key on the keyboard (e.g.,KeyZ).

input.addEventListener('keydown', (e) => {

console.log(`key=${e.key}, code=${e.code}`);

});

Event Delegation

The event delegation refers to the technique of using event bubbling to handle events at a higher level (Parent element) in the DOM than the element on which the event originated (Child).

<ul id="menu">

<li><a id="home">home</a></li>

<li><a id="dashboard">Dashboard</a></li>

<li><a id="report">report</a></li>

</ul>

Instead of doing (adding event listener to each child)

let home = document.querySelector('#home');

home.addEventListener('click',(event) => {

console.log('Home menu item was clicked');

});

let dashboard = document.querySelector('#dashboard');

dashboard.addEventListener('click',(event) => {

console.log('Dashboard menu item was clicked');

});

let report = document.querySelector('#report');

report.addEventListener('click',(event) => {

console.log('Report menu item was clicked');

});

do this instead (event listener only on parent, use event bubbling)

let menu = document.querySelector('#menu');

menu.addEventListener('click', (event) => {

let target = event.target;

switch(target.id) {

case 'home':

console.log('Home menu item was clicked');

break;

case 'dashboard':

console.log('Dashboard menu item was clicked');

break;

case 'report':

console.log('Report menu item was clicked');

break;

}

});

Event() constructor & dispatchEvent()

create own event with Event constructor and dispatch (occur) it with dispatchEvent method. Example:

let btn = document.querySelector('.btn');

btn.addEventListener('customEvent', function () {

alert('Custom Event Occured');

});

let customEvent = new Event('customEvent');

btn.dispatchEvent(customEvent); // triggers the event on btn

Event constructor

let event = new Event(type, [,options]);

type

is a string that specifies the event type such as 'customClick'.

options

is an object with two optional properties:

bubbles: is a boolean value that determines if the event bubbles or not. If it istruethen the event is bubbled and vice versa.cancelable: is also a boolean value that specifies whether the event is cancelable when it istrue.

By default, the options object is { bubbles: false, cancelable: false}

let customEvent = new Event('customEvent', {

bubbles: true,

cancelable:true,

});

Event class tree

Event (base type)

|

+-- UIEvent (inherits from Event)

|

+-- MouseEvent (inherits from UIEvent)

+-- TouchEvent (inherits from UIEvent)

+-- FocusEvent (inherits from UIEvent)

+-- KeyboardEvent (inherits from UIEvent)

It is better to be more specific while creating custom events. Let’s say for a custom click event we should use MouseEvent() constructor. It will also give us extra methods like clientX, clientY, etc.

isTrusted

If the event comes from the user actions, the event.isTrusted property is set to true. In case the event is generated by code, the event.isTrusted is false. Therefore, you can examine the value of event.isTrusted property to check the “authenticity” of the event.

Custom Events

Custom events allow you to decouple code execution, allowing one piece of code to run after another completes.

For example, you can place event listeners in a separate script file and have multiple listeners for the same custom event.

General structure

let event = new CustomEvent('eventName', {

detail: { /* custom data */ }

});

Example

function highlight(elem) {

elem.style.backgroundColor = 'yellow';

let event = new CustomEvent('highlight', {detail: { color: 'yellow' , bordercolor: `black`} });

elem.dispatchEvent(event);

}

let div = document.querySelector('.note');

div.addEventListener('highlight', (e) => {

console.log(e.detail.color); // Output: yellow

div.style.border = `solid 1px ${e.detail.bordercolor}`; // black border

});

highlight(div);

instead of doing this:

function highlight(elem, callback){

const bgColor = 'yellow';

elem.style.backgroundColor = bgColor;

if (callback && typeof callback === 'function') {

callback(elem);

}

}

let note = document.querySelector('.note');

function addBorder(elem) {

elem.style.border = "solid 1px red";

}

highlight(note, addBorder);

Objects

collection of key:value pairs, conatined inside {}

NOTE: Trailing comma is helpful, ie comma after last property

NOTE: Empty property declaration not allowed. do

property: nullif you need

Create object

empty object

let user = new Object(); // "object constructor" syntax

let user = {}; // "object literal" syntax

another example

let user = {}; // creates empty object

user.name = "John"; // adds property name

user.surname = "Smith"; // adds property surname

user.name = "Pete"; // update property name

delete user.name; // delete property name

Deleting properties

delete user.age;

Multiword properties

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

"likes birds": true // multiword property name must be quoted

};

Square brackets

Must for multi-word properties.

let user = {};

// set

user["likes birds"] = true;

// get

alert(user["likes birds"]); // true

// delete

delete user["likes birds"];

Square brackets support all type of strings, whereas dot (.) operator doesn’t

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

};

let key = "name";

alert( user.key ) // undefined

alert( user[key] ) // John

Computed properties

let fruit = prompt("Which fruit to buy?", "apple");

let bag = {

[fruit]: 5, // the name of the property is taken from the variable fruit

};

alert( bag.apple ); // 5 if fruit="apple"

let fruit = 'apple';

let bag = {

[fruit + 'Computers']: 5 // bag.appleComputers = 5

};

Property value shorthand

The use of this is so common

function makeUser(name, age) {

return {

name: name,

age: age,

// ...other properties

};

}

let user = makeUser("John", 30);

alert(user.name); // John

that there is a shorthand to do the same

function makeUser(name, age) {

return {

name, // same as name: name

age, // same as age: age

// ...

};

}

let user = {

name, // same as name:name

age: 30

};

Property names limitations

For an object property, there’s no such restriction of the language-reserved words like “for”, “let”, “return” etc.

let obj = {

0: "test" // same as "0": "test"

};

// both alerts access the same property (the number 0 is converted to string "0")

alert( obj["0"] ); // test

alert( obj[0] ); // test (same property)

// obj[0] does not mean the first property

Property existence check

let user = { name: "John", age: 30 };

alert( "age" in user ); // true, user.age exists

alert( "blabla" in user ); // false, user.blabla doesn't exist

for…in iterator

let user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

isAdmin: true

};

for (let key in user) {

// keys

alert( key ); // name, age, isAdmin

// values for the keys

alert( user[key] ); // John, 30, true

}

Check empty object

function isEmpty(obj) {

for (let key in obj) {

// if the loop has started, there is a property

return false;

}

return true;

}

Order of properties

integer properties are sorted, others appear in creation order

let obj = {

3: "three",

hola: "pojo",

1: "one",

aah: "oni",

"2": "two",

};

console.log(obj);

// { '1': 'one', '2': 'two', '3': 'three', hola: 'pojo', aah: 'oni' }

// same order followed in for..in

FACT: this is the reason phone codes have “+” in front of them

Object Reference

in primitive variables

let data = 42;

// dataCopy will store a copy of what data contains, so a copy of 42

let dataCopy = data;

// which means that making changes to dataCopy won't affect data

dataCopy = 43;

console.log(data); // 42

console.log(dataCopy); // 43

but in objects

// obj contains a reference to the object we defined on the right side

const obj = { data: 42 };

// objCopy will contain a reference to the object referenced by obj

const objCopy = obj;

// making changes to objCopy will make changes to the object that it refers to

objCopy.data = 43;

console.log(obj); // { data: 43 }

console.log(objCopy); // { data: 43 }

but

let animal = { species: "dog" };

let dog = animal;

// reassigning animal variable with a completely new object

animal = { species: "cat" };

console.log(animal); // { species: "cat" }

console.log(dog); // { species: "dog" }

Constructor

function Player(name, marker) {

this.name = name;

this.marker = marker;

this.sayName = function() {

console.log(this.name)

};

}

const player1 = new Player('steve', 'X');

const player2 = new Player('also steve', 'O');

player1.sayName(); // logs 'steve'

player2.sayName(); // logs 'also steve'

Prototype

To check whether a object is an instance of a specific prototype or not from the above example:

Object.getPrototypeOf(player1) === Player.prototype; // returns true

Object.getPrototypeOf(player2) === Player.prototype; // returns true

Object.getPrototypeOf(Player.prototype) === Object.prototype; // true

// This means that Player.prototype is inheriting from Object.prototype

- The value of the Object Constructor’s

.prototypeproperty (i.e.,Player.prototype) contains theprototypeobject. - The reference to this value of

Player.prototypeis stored in everyPlayerobject, every time aPlayerobject is created. - Hence, you get a

truevalue returned when you check the Objects prototype -Object.getPrototypeOf(player1) === Player.prototype.

Add more items to the constructor:

Player.prototype.sayHello = function() {

console.log("Hello, I'm a player!");

};

player1.sayHello(); // logs "Hello, I'm a player!"

player2.sayHello(); // logs "Hello, I'm a player!"

- We can define properties and functions common among all objects on the

prototypeto save memory. Defining every property and function takes up a lot of memory, especially if you have a lot of common properties and functions, and a lot of created objects! Defining them on a centralized, shared object which the objects have access to, thus saves memory.

hasOwnProperty

player1.hasOwnProperty('valueOf'); // false

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty('valueOf'); // true

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty('hasOwnProperty'); // true

Inheritance

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.sayName = function() {

console.log(`Hello, I'm ${this.name}!`);

};

function Player(name, marker) {

this.name = name;

this.marker = marker;

}

Player.prototype.getMarker = function() {

console.log(`My marker is '${this.marker}'`);

};

Object.getPrototypeOf(Player.prototype); // returns Object.prototype

// Now make `Player` objects inherit from `Person`

Object.setPrototypeOf(Player.prototype, Person.prototype);

Object.getPrototypeOf(Player.prototype); // returns Person.prototype

const player1 = new Player('steve', 'X');

const player2 = new Player('also steve', 'O');

player1.sayName(); // Hello, I'm steve!

player2.sayName(); // Hello, I'm also steve!

player1.getMarker(); // My marker is 'X'

player2.getMarker(); // My marker is 'O'

Though it seems to be an easy way to set up Prototypal Inheritance using

Object.setPrototypeOf(), the prototype chain has to be set up using this function before creating any objects. UsingsetPrototypeOf()after objects have already been created can result in performance issues

Another example:

// Initialize constructor functions

function Hero(name, level) {

this.name = name;

this.level = level;

}

function Warrior(name, level, weapon) {

Hero.call(this, name, level);

this.weapon = weapon;

}

function Healer(name, level, spell) {

Hero.call(this, name, level);

this.spell = spell;

}

// Link prototypes and add prototype methods

Object.setPrototypeOf(Warrior.prototype, Hero.prototype);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Healer.prototype, Hero.prototype);

Hero.prototype.greet = function () {

return `${this.name} says hello.`;

}

Warrior.prototype.attack = function () {

return `${this.name} attacks with the ${this.weapon}.`;

}

Healer.prototype.heal = function () {

return `${this.name} casts ${this.spell}.`;

}

// Initialize individual character instances

const hero1 = new Warrior('Bjorn', 1, 'axe');

const hero2 = new Healer('Kanin', 1, 'cure');